Background

Scenes from the Project

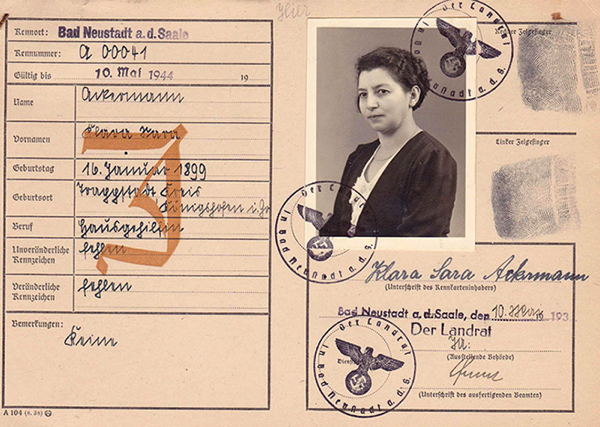

Case Study

In September 2013, a joint high school exchange program of German and Israeli students set out to restore, renovate and document the abandoned Jewish cemetery of Bad Neustadt an der Saale, where all traces of a once thriving Jewish community vanished following the annihilation of the Jews during World War 2. The exchange program between the high schools Mikve Yisrael High School (Holon, Israel) and the Bad Neustadt Rhön Gymnasium (Bad Neustadt a.S., Germany) has existed for over twenty years. The content of the program was traditionally one of cultural exchange. The documentation program that took place was the first attempt to address the question of the past.

Outcome

The student's documentation of the cemetery brought to the table new information which can be used for research. The documentation cards give us an idea of how many men, women and Children were buried. In some cases we can learn causes of death. Some leaders of the community have become evident: Teachers, doctors, people who were known to give charity etc.

From the places of birth stated on the grave we learned where people emigrated from.

By reading what people chose to engrave we can learn what they wanted to emphasise. A very interesting example are a few graves of men which mention the unit they fought in during World War One. This teaches us of the identity in regard to national affiliation.

This information needs to be treated carefully, just like any text. Questions need to be asked on motives and social structures. But with a carful analysis that cross references the documentation material with archives and local knowledge, much can be learned.

This cemetery is one of many in Bavaria that is not documented and many of the graves are already unreadable. The main initial goal of the project was to clean up and map out the cemetery and to document each grave. Already at this stage, the joint work of students proved to be a pathway to asking questions about personal and communal identity, about beliefs, preconceptions and joint values. Furthermore, the information gathered was used to expand the knowledge about the Jewish community of Bad Neustadt. History books did not pay much attention to this small peripheral community. The tombstones were able to shed light on aspects the students would not be able to learn about through other written sources.

In September 2013, a joint high school exchange program of German and Israeli students set out to restore, renovate and document the abandoned Jewish cemetery of Bad Neustadt an der Saale, where all traces of a once thriving Jewish community vanished following the annihilation of the Jews during World War 2. The exchange program between the high schools Mikve Yisrael High School (Holon, Israel) and the Bad Neustadt Rhön Gymnasium (Bad Neustadt a.S., Germany) has existed for over twenty years. The content of the program was traditionally one of cultural exchange. The documentation program that took place was the first attempt to address the question of the past.

Outcome

The student's documentation of the cemetery brought to the table new information which can be used for research. The documentation cards give us an idea of how many men, women and Children were buried. In some cases we can learn causes of death. Some leaders of the community have become evident: Teachers, doctors, people who were known to give charity etc.

From the places of birth stated on the grave we learned where people emigrated from.

By reading what people chose to engrave we can learn what they wanted to emphasise. A very interesting example are a few graves of men which mention the unit they fought in during World War One. This teaches us of the identity in regard to national affiliation.

This information needs to be treated carefully, just like any text. Questions need to be asked on motives and social structures. But with a carful analysis that cross references the documentation material with archives and local knowledge, much can be learned.

This cemetery is one of many in Bavaria that is not documented and many of the graves are already unreadable. The main initial goal of the project was to clean up and map out the cemetery and to document each grave. Already at this stage, the joint work of students proved to be a pathway to asking questions about personal and communal identity, about beliefs, preconceptions and joint values. Furthermore, the information gathered was used to expand the knowledge about the Jewish community of Bad Neustadt. History books did not pay much attention to this small peripheral community. The tombstones were able to shed light on aspects the students would not be able to learn about through other written sources.

This project is the outcome of an earlier and important program: Journey into Jewish Heritage, aimed at documenting lesser known Jewish communities around the world.

Under the initiative of Professor Stefan Simon, three former students, Eyal Tagar, Idit Ben Or and Tomer Appelbaum joined the Israeli and German high school students and instructed them in the methodology of documenting cemeteries.

Under the initiative of Professor Stefan Simon, three former students, Eyal Tagar, Idit Ben Or and Tomer Appelbaum joined the Israeli and German high school students and instructed them in the methodology of documenting cemeteries.