Hildegard Wehner

Interview (2013) with Ms Hildegard Wehner (born in 1923), Bad Neustadt

This interview was conducted by students of the Rhön-Gymnasium on March 1st 2013. In October 2014 it was revised by Ms Wehner before its publication on this web site.

Yes, of course, we used to play with the Jewish kids, for example with the three girls of the Friedmanns. The oldest one was Margot, the second one Gertrud and Ruth was the youngest. There were also the Kupfersbergers, […] Mr. Kupfersberger had a tailor’s workshop at the Market Place […] and we would go there with the girls and play together. […] And then suddenly one day we were told that we weren’t allowed to talk to them anymore. That was around 1933/1934, it was the time when the Jews were already pushed aside a little bit. And the girls, I think, went to England in 1936, but only the girls, the parents were still here. […]

We wanted to ask you about the Jewish school especially.

They had a normal school down there in the Storchengasse, near to the Bauerngasse.

And next to it there was a Jewish doctor, Dr. Guggenheimer. He stayed there for a long time even, to help the poor Jews. He emigrated rather late […]. In the end he got out of the country somehow.

By the way, he operated on me as well, when Dr. Schmitt was absent. […]

Do you have any more memories of Mr. Guggenheimer?

Yes, he was always there when somebody called him. Also he went to “Aryan” people often. He was a very quiet man, never conspicuous. He really was a very good doctor, I have to admit. Also he was quite a kind person. […]

Was the notion of the hated Jew drummed into your head at school?

When I was at school it wasn’t that spiteful yet. I went to school until 1937. Then I attended a boarding school. At this time it wasn’t of that immediate interest yet. It came up with the “Kristallnacht“ in 1938, then the hatred did start. Before that you could read it here and there sometimes that you should not buy from them.

And we had a lot of Jewish shops here. For example there was the “Oberer Sichel” (“Upper Sichel“) whose owner’s name was Nussbaum. […] They had mainly high quality goods, for trousseaus, for example, and they had many customers in those days. And then there was the “Unterer Sichel” (“Lower Sichel“), it was where you can find „Wöhrl“ today.

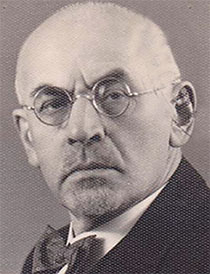

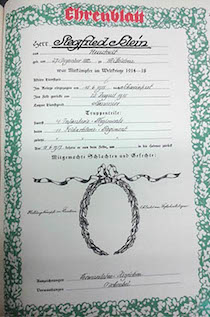

Then there was Klein’s department store in the Hohnstraße where until recently you could find the „Hohntor-Apotheke”. […] And where you can find the hairdresser Blümm now, the house of Appl-Wagner, in the Storchengasse/Spitalgasse there was also a Jewish house, the “Stern’s house”: Its owner’s name was Klein and he was in Wold War I and I think he lost both his legs, as he was always sitting in a wheelchair. He had got the EK1 („Eisernes Kreuz“ first class, German war decoration, translators’s note). He was respected and honoured, but suddenly it was all over, then he was quite a poor chap indeed and the family had to suffer a lot at that time.

Talking about the name Klein: Is Mr. Klein the father of the Klein family who keeps occurring now again and again? With the children having been brought to safety in England?

No, they had come, if I am right, from Unsleben in those days. There were so many people with this name. They were taken in and accommodated in that house of the other Klein family, that was and is a big building. They got concentrated and had to give up and leave their houses one after the other. […]

Up in the Bauerngasse (“Peasants’ Lane”) there was the Synagogue, and it was to be demolished in the “Kristallnacht”(“Crystal Night”), I have heard. But then Ingebrandt (the mayor and “Kreisleiter”, highest NSDAP official in a “Kreis”, translators’s note) gave the order to use it as a granary, which in fact saved the building. […]

In the Judengasse (“Jews’ Lane”), now Apothekengasse (“Pharmacy’s Lane”), strangely enough there were almost no Jews at all. Where there is the surgery today, in the Zeißner house, there used to be a Jewish shoe shop. Its owners were the Platts, a couple without any children and, as far as I know, the only Jews in that lane. […]

Did you witness anything of the Jews running the gauntlet to the station? With children howling and yelling at them on their way there?

We saw that from the window, poor people really. Well, there was a certain Ottensoser who lived up there in the Kellereigasse in a very small house, today it’s a part of the “Villsche Stiftung” (“Vill’s Foundation”), an old people’s home. Quite common people they were, having a child suffering from a heart disease, which you could tell from his bluish finger nails. I remember feeling ever so sorry for him! At the time of the deportation the kid was sitting on the steps outside our shop with his little rucksack on his back. Then they were all rounded up, everyone was carrying their little suitcases and then they were driven out of town and there was quite a number of people coming along with them, cheering and swearing at them and calling them names.

And is it true that the children had no idea why they were supposed to cheer?

I don’t know, I was much older, anyway, I was with my mother and she was just shaking her head.

There’s something else, too, I’ve got to tell you: In those days of everybody suffering want but the Jews in particular, some of them came along nearly starving and my mum told them to come again when the shop would be closed, in the dark, and then she would give them the bread that had not been sold that day at the backdoor. And then, at night, she’s looking outside in the back and there is a whole line of Jews and she said: For heaven’s sake, you mustn’t do that, I’ll give you what is left, no problem about that, but next time only one, not more than two must come and get it to avoid notice, otherwise I’ll be in for trouble. And the following day there was only one to pick it up and my mother said: You have to divide it among those who need it most.”

Yes, my mother did do a lot for them, also because they had been customers of ours in the bakery before. There was something called “Berches”, a white bread with a kind of plait on its top and poppy seed all over it. I don’t know why it was called “Berches”, but they got that every Saturday. Well, we had many Jewish customers, you can’t deny that. Why should you, anyway, as we were glad to sell our products.

And can you remember any other people helping the Jews, apart from your mother?

Yes, quite a lot. Where Jews were living, unless they were having a quarrel with each other, like it was with the Kupfersbergers, they shared bread and butter and everything they had with them still in the end. After all they were hungry.

At the weekend the Jews would have their special days, the Sabbath days. At the Friedmanns they had prepared everything for that purpose and Irmgard and I, always the two of us, we went down, because we always found that interesting. And then we had to light the stove with matches so that they didn’t feel cold, and the lamps, too. Everything else had been prepared. And there the Jews were sitting with their hats on and had their Schabbes.

Yes, because they aren’t allowed to work on Sabbath, somebody else had to do that and light the lamps and the stove for them. […]

With the Friedmanns it was the same. They had two tables, one was “kosher” and the other one was “trever”. That’s what they called it. And on one particular table only kosher things were allowed. An animal, a goose for example, was made kosher by draining its blood from it. That was “schächten”, slaughter according to Jewish rites. That was their religious belief.

And Jew Friedmann somehow seemed to be particularly religious, because so many of them used to assemble at his place […]. Or the, what’s its name, the “Laubhüttenfest” (Feast of Tabernacles). So there was a “Laubhüttenfest”, too. He had a hut built of leaves (Sukka) in his backyard. Those are memories of those days.

That was all commonly known, wasn’t it?

Yes, it was, because you could see it. And at the Kupfersbergers’ home I would come and go because we had been friends from early childhood.

Did you actually go into one of those huts once?

No, I didn’t, for heaven’s sake. That was always taboo for us. That was out of the question. We could go only where they allowed us to go, for example into that particular room where we had to turn on the switches or make fire, that was o.k., but anywhere else, no. That was not possible, you couldn’t witness anything happening somewhere else.

Did you actually once enter a synagogue or not?

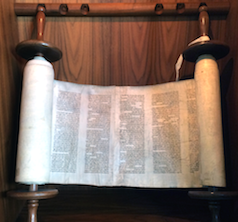

No, never ever. What I know is that in those days when the synagogue was cleared, Reverend Friedrich took care of all those Torah scrolls, those Jewish scrolls and brought them all into the church.

Rev. Friedrich was a distant relative of my mother’s from Königshofen. And so we were able to see him, the Reverend, after his death. They had injured him very badly, they had whipped him. My mother and I were in his house. Except the hands and the face, everything else, the legs and all the rest had been beaten up brutally. […]

What did people know here about the concentration camps? Did they know what was going on there?

A common phrase was: “If you can’t keep your mouth shut you’ll be taken to Dachau! So watch it and don’t tell such things! If you aren’t silent, you’ll be taken to Dachau.” And those who had been to Dachau and returned from there never said a word about it in their lifetime.

But people did know that all the Jews were in these camps, didn’t they?

We didn’t know that, but we thought so. That they were rounded up and that they would be taken somewhere, everybody knew. […] Poor people, that really was a bad time for them.